To envision a just and regenerative economy; apply the concepts locally; then share the results for broad replication.

Founded in 1980 the Schumacher Center for a New Economics works to envision the elements of a just and regenerative global economy; undertakes to apply these elements in its home region of the Berkshires in western Massachusetts; and then develops the educational programs to share the results more broadly, thus encouraging replication.

We recognize that the environmental and equity crises we now face have their roots in the current economic system.

We believe that:

- a fair and regenerative economy is possible and that citizens working for the common interest can build systems to achieve it

- our natural commons are best held by the regional community

- money issue can be democratized

- ownership should be more diversified and that labor should have a part in the ownership structure

We favor the face-to-face relationships fostered in local economies. We deliberately focus on transformative systems and the principles that guide them.

Our Logo

The Schumacher Center's new branding was created by Andrew Plotsky of Farmrun.

Below is his description of why he designed the Schumacher Center's logo the way that he did, and what his inspiration was.

The Schumacher Center for a New Economics is a visionary organization that builds on the ideas concepted by the economic counterculturist E. F. Schumacher - whose vision of a new economics revolved not around fossils, industry, capital and endless growth, but rather local communities, land, and endemic resources.

In the course of redesigning the logo system for Schumacher Center, it is a goal to build a new visual identity that is honest and appropriate to the unique vision the organization embodies - simultaneously contemporary & future focused, and traditional & historic in scope. The philosophy embodied is distinctly sensible, just and harmonious, though not at the expense of complexity. It is bold in its divergence from conventional rhetoric, and brave in its conviction in the vision. There is a strong theme in the nature and mission of the organization - both of which are split in threes. The nature of Schumacher Center is to address people, land and community; the approach is to embrace theory, philosophy and practice; while the mission involves envisioning, application and sharing. The visual theme of threes, triangles and confluent repetition were thus a strong theme in this round of design concepts.

In many of Schumacher’s talks and writings, he presents Time as an ingredient missing in the cocktail of conventional industrial economic rhetoric, and one that is essential to the New Economic vision that he puts forth, which values people, planet and place. Things take time.

This design is a combination of an hourglass and prism - two well regarded and iconic symbols, traditionally endowed with meaning, presented in a new and modern take that embodies Schumacher Center’s legacy, mission and operations. The hourglass, being representative of the time requisite to invest in people, land and community to develop our new economic system, is also prism, a device of supreme simplicity, of the natural world, which reveals the three main subjects and avenues that compose the unified vision of Schumacher, and mission of the Schumacher Center. The split rays of the mission implicate the dynamic and multifarious operations that Schumacher Center pursues under a single, unified organization:

PEOPLE / LAND / COMMUNITY

ENVISION / APPLY / SHARE

THEORY / PHILOSOPHY / APPLICATION

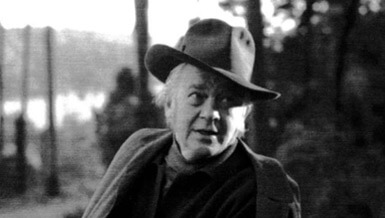

E. F. Schumacher's World View

In 1976 the economist Fritz Schumacher spoke at Findhorn in Northern Scotland in an address as relevant today as it was then. Historically, he noted, we are at the end of three distinct eras—first a Descartian informed world view which valued what was known through the senses above spiritual knowledge and encouraged an accumulation of things as a path to happiness; second a sociological system shaped by the industrial revolution’s division of labor which led to the degradation of the human being; and third an economic system driven by a belief in infinite resources and quick technological fixes, resulting in a ravaged eco-system.

As these old eras draw to a close, bankrupt, he went on, we need to regain a traditional understanding of what is good, true, and beautiful and so inform our actions to build a new era that acknowledges the wholeness of life. It is not a single-issue crisis that we face—not just an energy crisis, not just a nuclear crisis, not just an ecological crisis or sociological or political or cultural—our whole way of life is at stake and solutions must be developed and implemented simultaneously at many levels. He calls on the audience to first work to foster a new world view in themselves, diagnose what can be done, see if others are already engaged in that rebuilding work and support them, and then act themselves, if even in a small way.

Exhibiting his characteristic charm and humor, a historic breadth of thinking, the integrity of his own example, a belief in his audience and the capacity of the human spirit to seek solutions and bring about change—this Findhorn address shows Schumacher at his best.

Listen to Schumacher's talk The World Crisis and the Wholeness of Life.